Millions of people still lack a copy of God’s Word in their own language, but a new methodology by Wycliffe Associates is rapidly changing that.

By Michael Foust

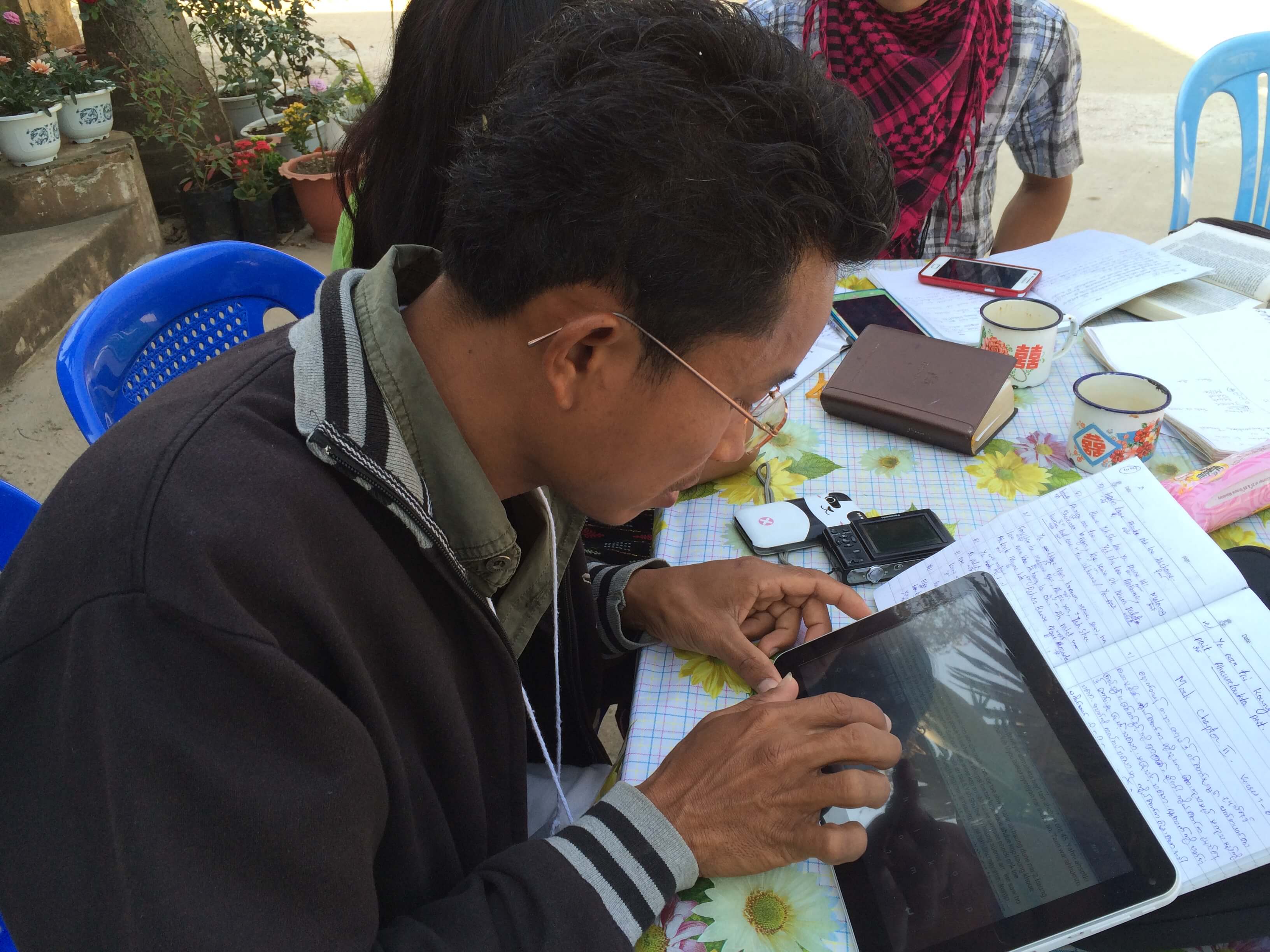

The villagers clutched pens and paper, eager with anticipation and excitement. But they took their task seriously, knowing that the name of Christ — and the souls of their people — were at stake.

At 117 strong, this group of Christians had gathered in a Southeast Asian location for a special workshop on Bible translation. Their goal was simple: to give their people the first-ever Bible translated in their own language. Their enthusiasm was contagious … and convicting.

Less Than Half of All Languages Have a Bible Translation

More than 2,000 years after Christ walked the Earth and commanded His followers to “make disciples of all nations,” millions of people around the world still can’t read about Him. Of the 7,097 languages that are spoken, only 2,932 have the Bible translated in their language, according to data by the translation ministry Wycliffe Associates. The reason for that is both simple and complex, but progress — rapid progress — is being made.

In 2014 Wycliffe Associates launched a new methodology that dramatically decreased the time it takes to translate Scripture from one language to another. Whereas in the past a single missionary often spent an entire career translating the Bible — sometimes taking 20 to 30 years to do so — the new method allows Bibles to be translated in as little as a few weeks. Even better: It doesn’t require computers.

MAST Empowers Local Christians

The method, dubbed “MAST” (Mobilized Assistance Supporting Translation), empowers local Christians to do the translating. They are trained on site at workshops by Wycliffe officials and then devote the ensuing weeks and months to the project.

“It’s an unprecedented pace for the completion of Bible translation compared to traditional methodologies,” Bruce Smith, president and CEO of Wycliffe Associates, told Today’s Christian Living. “The people who are anxious for God’s Word in their language are thrilled with it.”

For the 117 Southeast Asian Christians, the method allowed them to have a copy of the Old Testament, in their language, in merely two weeks. The New Testament was completed by a smaller group of people in a similar time.

MAST has impacted 730 languages during the three years it’s been used.

Incredibly, the local Christians did it all by hand, meticulously translating Scripture the old-fashioned way, with pen and paper.

“This is a group of people who were very serious about having the entire Bible in their language as soon as possible,” Smith said. “They basically handed their [handwritten copies] to us and a group of keyboarders and said, ‘Please input this into the computers for us so we can have it in digital format.’”

The skills and steps required to translate a Bible under

the MAST model are independent of computers or the

Internet, but technology does help speed the transmission

and distribution of the text that is already translated.

Plans to Start 400 New Translations in Wycliffe’s 50th Anniversary Year

Wycliffe launched 315 new Bible translation projects last year and assisted in the completion of 58 New Testament translations — all using MAST. The organization plans on starting 400 new Bible translations this year, which just happens to be the organization’s 50th anniversary.

“The time it takes to complete a translation,” Smith said, “depends on how many translators” are involved.

“We have had five different language groups who have brought 30 or more translators to their workshop and have completed a New Testament translation — both drafting and checking — in two weeks,” he said. “You can’t leap to the conclusion that everyone is going to get done in two weeks, though. Many have brought far fewer, but we have more than 300 that are projecting the completion of their New Testament in less than two years.”

Two years may seem like an eternity, but in the translation world, it’s tantamount to a speedy cheetah. Barely a decade ago, translations were taking far longer.

The Translation Bottleneck Opened

The old model of translation — “one translator, one language, one lifetime,” as Smith describes it — had several weaknesses. First, it was slow. The missionary first had to learn the language and the culture before the translation even began. Second, it depended on limited foreign resources, which sometimes meant that the most-used languages got priority. Of the 7,097 languages in the world, some are spoken by only a few hundred people.

“A lot of these languages are languages that have been overlooked for Bible translation for a lot of years because they’re small or because they’re determined not to be strategic by a variety of people,” Smith said.

The traditional model of translation, Smith said, is one of the reasons that millions of people still lack a Bible in their language.

“Basically, it was a problem where scarce foreign resources are the bottleneck,” he said. “That has been the limiting factor on the spread of Bible translation. Now that Bible translation can be done by the local church — by the local body of Christ — that bottleneck doesn’t need to exist anymore. And we believe that within just a few years, everybody in the world is going to have Scripture in their language.”

Technological advancements have played little role in MAST’s success stories. That’s because the skills and steps required to translate a Bible under the MAST model are independent of computers or the Internet.

Tablets for National Translators (TNTs) provide translators

with a tool to get Scripture they have translated into their

own language saved and ready for printing.

Oral Translation for Those With No Written Language

But that doesn’t mean technology has played no role in translation. If a people group is largely illiterate — or if it has no written language — oral translations are employed. This involves recording a Bible in digital MP3 format, which is then transferred to and played on smartphones.

“Local Christians will get an audio translation in a language they’re familiar with, and they’ll translate from the audio into an oral translation in their language — and just leave out the whole intermediate written step,” Smith said. “Then, at a later point in time, they can work on a written Bible.”

The smartphone, he said, is placing Scripture within reach of “everybody in the world.”

“A lot of oral translations in the past have been put onto little players that could be either cranked mechanically or could be run with solar or something like that,” he said. “Nowadays, everybody has a cell phone, so all they need to do is download the MP3 file, either from the Internet or from a SIM card if they have a regular phone.”

For oral language groups (those with no written language),

local Christians will get an audio translation in a language

they’re familiar with, and they’ll translate from the audio

into an oral translation in their language — and omit the

intermediate written step. Then later, they can work on a

written Bible.

Limitations of MAST

The MAST model is not without controversy, though. In 2015, several organizations involved in Bible translation, including Word for the World International, monitored a MAST translation and released a report expressing concern about “major inconsistencies in style and terminology” due to the use of multiple translators on the same project. The groups said the report “should not necessarily be interpreted as a ‘blanket assessment’ of other MAST translations.”

Smith has considered the arguments against MAST but remains committed to the model.

“Anytime humans are involved — regardless of who those humans are — the potential for error is real,” he said. “But let’s not pretend that because we are educated Westerners that, somehow, that precludes us from making mistakes. The local body of Christ is the best judge of Bible translation quality in their language.”

MAST has impacted 730 languages during the three years it’s been used.

“Our experience with these 730 language groups is that the closer you get to the actual people and location where they are without Scripture, the more excited they are to have MAST to get Scripture sooner rather than later,” Smith said. “Just listen to the people who have spent generations without Scripture — and who are dying to have it.”

WYCLIFFE CELEBRATING 50th ANNIVERSARY

Fifty years ago this year, three men — Bill Butler, Dale Kietzman, and Rudy Renfer — examined the world of Bible translation and discovered a major problem. Bible translators, they noticed, were spending an inordinate amount of time on tasks that had nothing to do with translating God’s Word. And that, in turn, was delaying the translation of Scripture. So, the men did something about it, launching an organization called Wycliffe Associates. It was named for the famous 14th-century Bible translator John Wycliffe.

“For 50 years we’ve been supporting other people who are doing Bible translation,” said Wycliffe Associates president and CEO Bruce Smith. “We do that with infrastructure, technology, funding, education, training — any kind of resources to help Bible translation move forward.”

For example, Wycliffe is helping churches in remote and dangerous parts of the world through a new technology it calls Print on Demand (POD), a high-speed digital printer that is large enough to print Bibles but small enough to be hidden in areas where Christianity is banned. Each POD costs about $15,000.

Sometimes, PODs are used to print the very first Bible in a specific language. Of the 7,097 languages in the world, hundreds still lack a Bible. Smith is confident that within a few years, every language will have a Bible.

“There are more Christians living outside the West than there are in the West,” Smith said. “The church is now global. It’s in the East, it’s in Asia, it’s in Africa, it’s throughout the Pacific. Everywhere we go, we realize that the church is already there.”

For more information, visit WycliffeAssociates.org.