By Michelle Adserias

It’s impossible to measure the impact one person’s life, lived fully devoted to God and his or her divine assignment, has on the world. Thousands of unsung saints have left their mark in their sphere of influence, leaving this life behind without knowing the full impact of their faithfulness. A rare few see their work completed. Even these don’t live to see the ripples die.

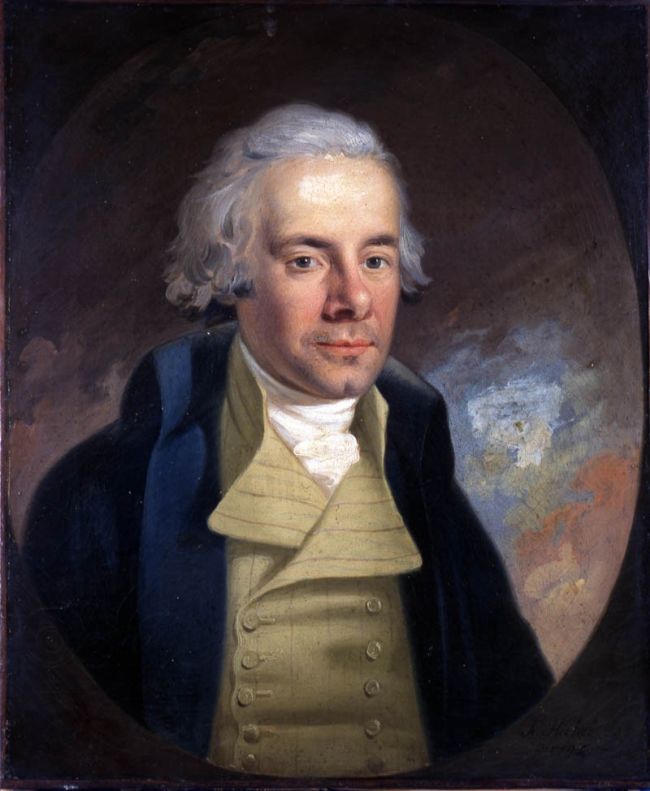

William Wilberforce is one such man.

Born into wealth in 1759, he knew the luxuries of life. When his father died, young William went to live with an uncle and aunt who were also wealthy. They introduced him to the evangelical preaching of former slave trader, John Newton, which greatly concerned his mother. She did not want him influenced by Methodist teachings, so she enrolled him in a private school and moved him to York.

In 1776, William began his higher education at St. John’s College in Cambridge. They were not as productive as he had hoped. His tutor demanded little of him, academically, which gave him time and money to fritter away on entertaining himself and others. He had a quick wit, natural eloquence, endless energy, and winning charm — all of which made him popular among his peers.

One of his closest friends was fellow student, William Pitt. They often watched Parliament from the gallery and talked of the day they would one day sit on the floor and be part of the proceedings. It isn’t surprising, then, that William Wilberforce put in his bid for a seat in 1780 when he was just 21 years old. Surprisingly, he won.

By his own admission, those early years in Parliament were wasted. He lacked direction and conviction. But that all changed in 1784 when he invited his acquaintance, Isaac Milner, to travel to the French Riviera with his family.

Milner was bright, articulate and a devout Christian who embraced Wesley’s evangelical teachings. Though William was known as a religious man, he was confronted with his need for a Savior. His conversations with Milner opened William’s eyes to wealth’s emptiness and the general lack of direction in his life. He began to understand that we are purchased with Christ’s blood and must lay down our lives, take up our cross, and follow Him. His inward battle was finally resolved on Easter in 1786 when he surrendered his life to his Savior and his new life in Christ began.

William began praying for clear direction in his life. He considered stepping out of the public eye, leaving Parliament. This idea was put to rest when several friends approached him to lead the campaign to abolish slavery. Even his friend William Pitt, who had become Prime Minister, encouraged him to take on the fight. God was directing him to stay where he was. But no one prepared this idealistic young man for the long, rigorous battle that lay ahead.

Charles Wesley, Thomas Clarkson, Hannah More and others had begun pointing out the evils of slavery, appealing to the moral conscience of the nation. But no one had attempted to take on the slave trade, which contributed an enormous amount to the British economy, on a national level.

The opposition was fierce. Many proponents of the slave trade feared financial ruin if it was abolished. They vilified William at every opportunity but he was undaunted. Support from several key members of parliament and England’s spiritual leaders helped him continue the fight. On his deathbed, John Wesley wrote to William, “I see not how you can go through your glorious enterprise in opposing that execrable villainy, which is the scandal of religion, of England, and of human nature. Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you?”

But slavery was not the only cause William took on. His desire was to raise the moral fiber of the nation by bringing the needs of single mothers, orphans, chimney sweeps, even abused animals to the attention of the nation in hopes of caring for the marginalized. In all, he gave away a fourth of his income to support 69 philanthropic causes. When Charles Wesley passed away, William supported his widow until her death.

This powerful man suffered from illness. His body was frail, inside and out. He had poor vision, suffered from bouts of colitis, and sometimes needed a metal frame to support his body. The only treatment for such ailments at the time was laudanum, a derivative of opium. In time, he became addicted and suffered from hallucinations, depression and, eventually, partial amnesia.

After a 20-plus year battle, slavery was abolished in Great Britian, 283 votes to 16. Wilberforce wept with joy, the work God assigned to him, the work that took a toll on his health and wealth, was nearly done. He relinquished his seat in Parliament.

In July of 1833, the final passage of the emancipation bill insured the end of Britain’s slave trade. William died three days later. Parliament insisted William Wilberforce be laid to rest in Westminster Abbey and suspended business for his memorial service.

“If you love someone who is ruining his or her life because of faulty thinking, and you don’t do anything about it because you are afraid of what others might think, it would seem that rather than being loving, you are in fact being heartless.”

William Wilberforce

Information taken from Profiles in Faith: William Wilberforce at www.cslewisinstitute.org.