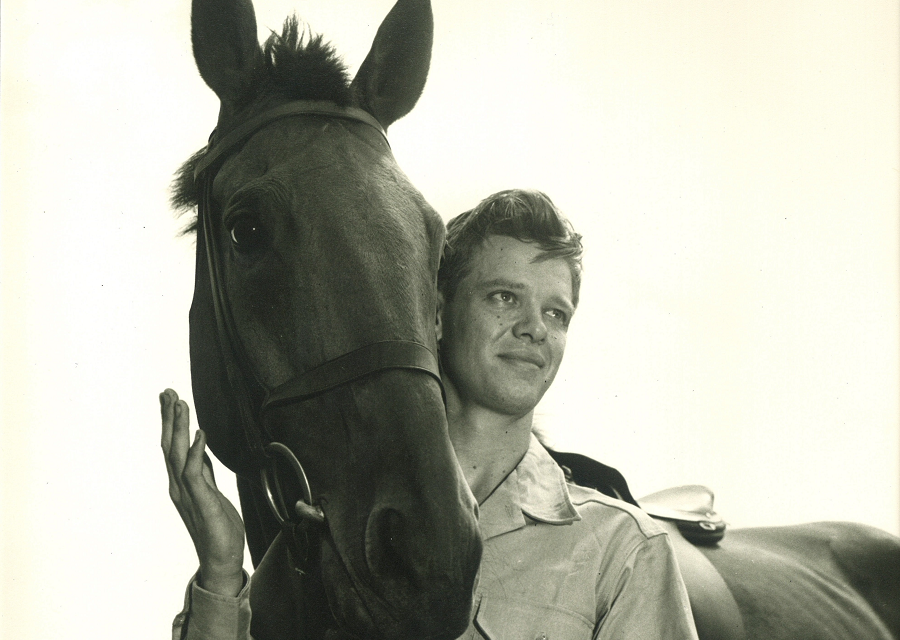

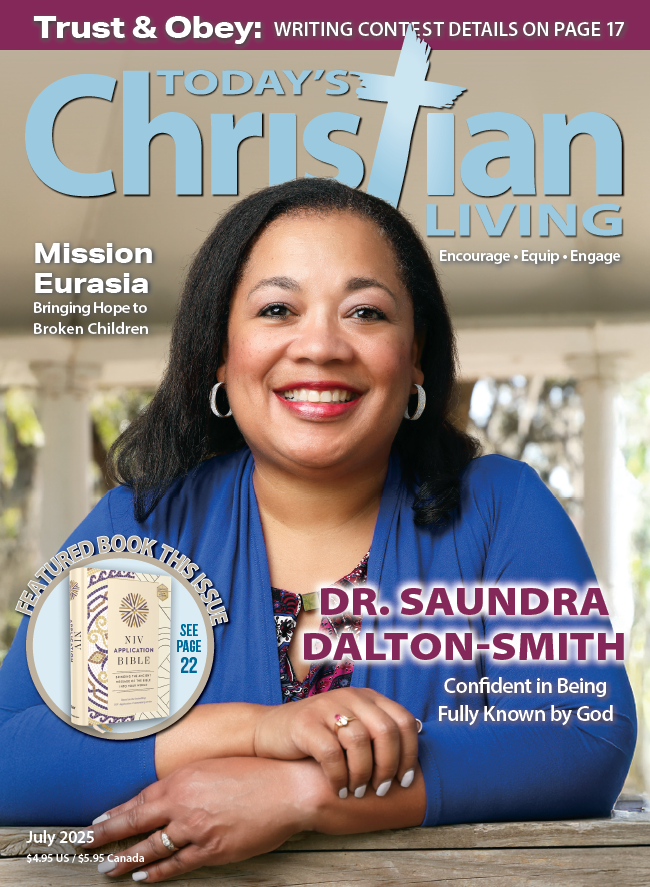

A Son of a World War II Hero Shares His Father’s Incredible Story of Courage and Sacrifice

By Walt Larimore

Like almost every boy who grew up in the 1950s and early 1960s with World War II epics on TV and at the movie theaters, I wanted to believe that my daddy had been a brave and courageous soldier when he fought in the war. Maybe he was an unknown hero or another Audie Murphy — someone I could boast about to my friends.

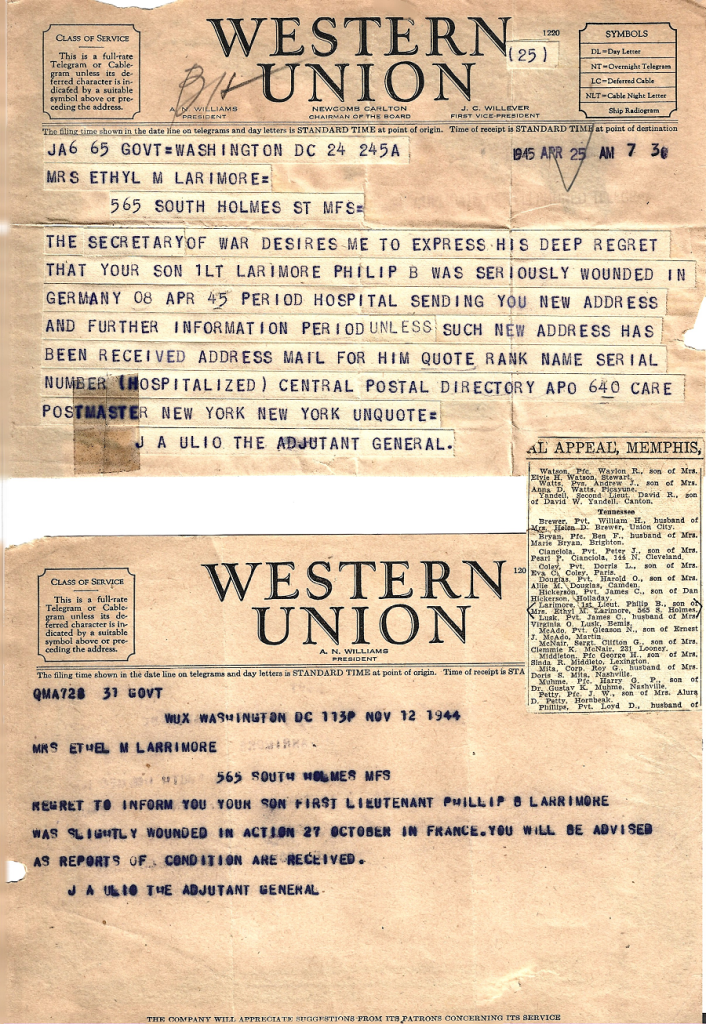

But since Dad never talked about his experiences as a soldier, I couldn’t match the tales other boys told when they bragged about their fathers’ exploits on the battlefield. When I asked Mom why, all she would say was, “He doesn’t like to talk about it.”

I now understand why. For frontline soldiers like my father, the war was indescribably horrible. I also knew that Dad’s right leg had been amputated only one month before the end of the war, so it made sense why he never wanted to talk about how he lost his limb.

Then, on his 50th wedding anniversary in 1999, we were sitting together when I casually mentioned to him that I had been asked to preach a Fourth of July sermon at our church on the topic “Freedom Isn’t Free.” I wondered if he might tell me a little more about his adventures during the war years.

Perhaps he was feeling nostalgic after a half-century of marriage and keeping his past concealed, but for whatever reason, he decided that was the right moment to share parts of a remarkable adventure when he fought in Europe alongside 2 million other young men. He strongly denied being a hero, however. “I was one of over 550,000 U.S. casualties in the European theater of operations,” he told me. “Of those, a little over a hundred thousand were killed in action. Son, those were the heroes. Not me!”

But Dad sure sounded like a hero to me when he showed me the shadow box in his office with some of his medals, including the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S. Army’s second-highest military decoration for soldiers who display extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force.1 Dad’s bravery was also evident when he told me about being part of an extremely risky top-secret mission far behind enemy lines near the end of the war that would save the world-famous Lipizzaner horses from near extinction.

But nothing topped Dad’s story of heroism when he described the day he lost his leg. After more than 15 months of non-stop fighting, he was commanding a frontline infantry company in April 1945 when they got caught in a firefight in a heavily wooded forest bordering the German village Rottershausen. German snipers nestled in towering firs were picking off his men one at a time. Machine gun nests hidden behind a camouflage of evergreen boughs kept the GIs pinned down. Simultaneously, well-camouflaged artillery fired projectiles into the canopy of hundred-foot-tall evergreens, timed to burst and rain splintered wood and white-hot shrapnel on the soldiers below.

In the chaos, Dad organized a counterattack to save his surrounded squad of men. But as he was laying down suppressing fire, an excruciating jolt of searing agony shot up his right leg. He hit the ground, groaning. Despite unbearable pain, Dad managed to roll himself into a shallow ditch.

From the safety of cover, he peeked over the edge. Scores of Germans, firing as fast as they could while screaming at the top of their lungs, were rushing toward him. When the Nazi soldiers were only 20 to 30 yards away, Dad lowered his head and played dead. Within seconds, the enemy soldiers leaped over the ditch and kept running.

His commander found him, close to death, as dusk fell. The surgeons saved his life but not his leg.

He was shipped to Lawson General Hospital in Atlanta for rehabilitation. It was there that Dad had a series of heartfelt conversations with a chaplain. My father was feeling incredibly depressed about his status as an amputee. His self-image was shattered; his future was uncertain.

After confessing these awkward feelings to the chaplain, he heard this life-altering advice: “Son, your wound will either make you a bitter person or a better person. It will either harden your heart or soften it. You will either be a person changed for the worse, or one who chooses to make the world better. In my opinion, the worst disability in life isn’t being disabled; it’s being disabled with a bad attitude. The Germans smashed your leg, but don’t let them shatter your heart, your talents, your gifts, your will, or your faith in God and His plan for you. The choice is really up to you.”

My father knew U.S. Army policy stipulated that any officer requiring an amputation would be forced to leave the military, but he felt led to formally fight this unjust policy. Although he knew it would be an uphill battle, it was one worth fighting.

Unfortunately, my father lost the final hearing in which he was told by one hearing officer, “Amputee officers simply don’t have a place in our Army!” Another exclaimed, “You’re a cripple! Mind you, a highly decorated cripple, but still a cripple!”

Dad determined that the Lord had another plan for him. He finished college and succeeded in a long career as a professor of cartography at Louisiana State University, where he published several books and founded and oversaw the Louisiana Geography Bee for years. He and Mom were also active members of St. Alban’s Chapel in Baton Rouge and enthusiastically involved in student ministry at the LSU Episcopal Student Center. Most of all, he was a loyal and devoted husband and father.

But Dad didn’t manifest his spiritual faith the same way I saw among my friends who were evangelical Christians. I remember asking him one time whether he felt he had a personal relationship with God.

He thought for a moment and told me, “In World War II, there was a popular phrase: ‘There are no atheists in foxholes.’ I remember reading that the Department of Defense reported that less than 1% of the armed forces said they were atheists. They also said that in the heat of the war, men who experienced intense combat were more than twice as likely to turn to prayer as those who did not. That was sure certainly true for me and my men.”

Dad reached into his wallet and pulled out an unfolded a piece of paper. “This is what I came to believe in combat,” he said.

No shell or bomb can on me burst, except my God permit it first.

Then let my heart be kept in peace;

His watchful care will never cease.

No bomb above, nor mine below, need cause my

heart one pang of woe.

The Lord of Hosts encircles me; He is the Lord of earth and sea.

My dad taught me that true spiritual faith — a true relationship with God the Father, through the sacrifice of Jesus — is manifested in our being controlled and empowered by the Holy Spirit in such a way that any true faith fills and overflows from our hearts and into our actions. True faith, he would say, is not merely worn on one’s shirt sleeve.

Dad’s prayers began to change. He asked for God’s guidance through the storms instead of a miraculous rescue from them. He prayed for a sense of peace to reign in his heart.

During the last few years of his life, Dad more frequently shared his stories and his faith with family and friends. He finally seemed to be at peace with his past and died a happy man, in his sleep, on October 31, 2003.

Despite Dad’s distinguished service, the only honor guard the Army could muster for his burial was two elderly volunteers wearing Veterans of Foreign War (VFW) caps, who played a cassette tape of “Taps” from a portable boombox. It wasn’t that the Army didn’t care or didn’t want to honor his fantastic feats on the battlefield, but this country was losing more than a thousand soldiers a day at the time. There was no way to keep up.

I remember what I was thinking that day, standing next to his grave with tears of gratitude streaking down my cheeks:

Dad, I always loved being your son. Now more than ever, I’m honored by it.

- The shadow box also included two Silver Stars, two Bronze Stars (both with the “V” device for valor), four Purple Hearts, the European Theater of Operations Campaign Medal with Four Bronze Stars and an Arrowhead, three Presidential Unit Citations, along with the American Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, and Combat Infantryman Badge, as well as a Fourragere and two Croix D’Guerre medals from the French. He was one of the youngest and most decorated frontline soldiers in World War II.

Walt Larimore has chronicled the exploits of his father, Philip B. Larimore, Jr., in At First Light: A True World War II Story of a Hero, His Bravery, and an Amazing Horse, which has been endorsed by numerous former generals like Gen. David Petraeus, Lt. Gen. William G. Boykin, and Gen. Ann E. Dunwoody; sports celebrities that include Mike “Coach K” Krzyzewski, Dan Reeves, and Joe Gibbs; nationally-syndicated columnist Cal Thomas, and multi-New York Times best-selling authors Jerry B. Jenkins and Marcus Brotherton. For more information, visit tinyurl.com/OrderAtFirstLight.