The Story of Faith Behind Captain Tammie Jo Shults’ Miraculous Landing of Southwest Flight 1380

By Dan Brownell

Tammie Jo Shults portrait photo courtesy Pam Akin

Just 20 minutes after Southwest Flight 1380 departed New York’s LaGuardia Airport on April 17, 2018, Captain Tammie Jo Shults faced the greatest challenge of her life. As the plane lifted off the runway, she had no way of knowing that in just a few minutes she would be wrestling a crippled Boeing 737 carrying 149 passengers and crew in a desperate attempt to bring it to a safe landing.

Mid-Air Disaster

Shortly after 11 a.m., cruising at 32,500 feet, bound for Dallas Love Field, the plane suffered a catastrophic engine failure. A turbine fan blade in the left engine suddenly snapped, shredding the engine and hurling shrapnel into the leading edge of the left wing and tail. The loss of all power in the left engine pushed the plane into a hard left roll and dive. The engine explosion was so violent that it also severed several hydraulic lines, a fuel line, and blew out a window in Row 14, resulting in explosive decompression. Simultaneously, the cockpit filled with thick haze, making it impossible for Tammie Jo and copilot First Officer Darren Ellisor to see anything. To make matters worse, the plane was shaking so violently that they could barely read the instruments even after the haze cleared.

The decompression also resulted in the loss of oxygen, so no one on board could breathe — including the pilots. Oxygen masks in the cabin automatically dropped, and while flight attendants assisted passengers in donning their masks, Tammie Jo and Darren donned theirs. The deafening roar of the wind made it difficult for Tammie Jo and Darren to communicate, and initially, they were forced to rely on hand signals until they slowed the plane and they could hear each other and the radio better.

Tammie Jo and Darren had trained for loss-of-engine emergencies for years, but this situation was so dire that even decades of rigorous training and simulations hadn’t prepared them for a challenge this extreme. A similar emergency years earlier underscores their peril. In 1989, United Airlines Flight 232 experienced a broken fan blade that severed all hydraulic lines governing flight controls. The pilots made an emergency landing in Sioux City, Iowa, but the aircraft was so difficult to control that it tumbled on landing, killing 111 of the 296 on board.

Regaining Control

While Darren flew the plane, Tammie Jo communicated with air traffic control to coordinate an emergency landing at Philadelphia International. Tammie Jo, the senior and more experienced pilot, then took the plane’s controls. Steering a heavily loaded 737 at high altitude, where the air is thin, requires a steady hand. “It’s a little like driving on black ice,” Tammie Jo explained. In this case, the challenge was greatly compounded by the power imbalance created by a single engine and the drag caused by structural damage. That made the aircraft “like trying to balance a BB on the top of a pin,” she said.

In emergencies, pilots consult detailed checklists that take them step-by-step through recovery procedures. But in a case like this — with a myriad of problems occurring simultaneously — landing the plane wasn’t simply a matter of following a checklist. “The combination of emergencies was unscripted, so addressing them was equally unscripted,” Tammie Jo explained. Tammie Jo and Darren had to rely on checklists they had on hand and on years of flying experience. “The damage on the side of the airplane continued to worsen as we flew the next 20 minutes, and it was damage that we’ve never practiced dealing with in a simulator. There was a lot of hands on…. there was no automatic anything,” she added.

Because the plane was 10,000 pounds overweight from unused fuel, she had to maintain a higher speed to overcome the plane’s increased weight and the drag from the wing damage. That meant using a Flaps 5 setting instead of Flaps 15. She also called for 180 knots airspeed, about 60 miles per hour faster than normal. These settings were a judgment call, but they turned out to be the right ones. If she had chosen differently, the aircraft would likely have crashed on approach.

As the plane settled onto the runway and rolled toward the end of the runway and the waiting emergency crews, Tammie Jo was recorded on the cockpit voice recorder rejoicing, “Thank You, Lord. Thank You, Lord, Thank You. Lord.” Shortly after, she texted “God is good” to a fellow pilot. These weren’t casual, offhanded comments. They were the words that naturally flowed from her because of her love for the Lord.

A Rock-Solid Faith

Tammie Jo’s faith has been her rock since childhood, and this was evident from her devotions early that morning of the flight. In retrospect, Tammie Jo realized that, through her Bible reading, God was preparing her for the upcoming trial later that day. He seemed to be speaking to her through Colossians 3:17, which says, “And whatever you do or say, do it as a representative of the Lord Jesus” (NLT). This came to pass in a way that she could never have imagined, as just hours after the landing she was speaking to media around the world.

Tammie Jo’s faith in Jesus is so deeply ingrained that she remained amazingly calm throughout the ordeal. When an EMT conducted a medical check on her shortly after landing, he was astonished that her pulse was normal. He commented that she had “nerves of steel.” She said, “I did have a mental calmness that I think was reflected in the calmness of my voice on the radio. But that wasn’t something of my doing. That was a gift from God.”

The Lord shines through Tammie Jo in her humility, as she’s quick to give credit to all who were involved that day. In her book Nerves of Steel, she said, “For the past year, I’ve stood in an unfamiliar spotlight because of what happened on Flight 1380, and I confess the attention makes me uncomfortable because I didn’t act alone. I had years of training and preparation. I had an amazing crew in the cockpit, courageous flight attendants in the cabin, attentive air traffic controllers, caring passengers themselves, skilled first responders, and a strong team on the ground that acted quickly and with compassion.”

Sovereignly Prepared for Crisis

Tammie Jo wasn’t originally scheduled for Flight 1380. She had traded flights with her husband, Dean, also a Southwest pilot, so she could attend their son’s track meet. Providentially, she had developed a unique set of flying skills years before as a Navy pilot through what — at the time — seemed a like an unwelcome assignment.

Tammie Jo standing beside her F/A-18 Hornet.

After Tammie Jo completed Navy flight school at NAS Corpus Christi, she learned to fly a variety of aircraft. Although most of the male pilots she served with treated her as an equal, some didn’t, including one commanding officer who spitefully assigned her a year-long stint training student pilots in Out-of-Control-Flight (OCF) procedures. OCF teaches pilots how to recover their planes from a range of scenarios in which the instructor intentionally loses control of the aircraft and the student has to recover. This is a duty no trainer wants because it often makes student pilots vomit.

Tammie Jo performed OCF procedures approximately 10 times with each student. By the end of the year, she had built up extensive experience in emergency recovery, including one training incident in which a rare malfunction caused the T-2 Buckeye to enter a spiral. The Buckeye was considered nearly impossible to put into a spin, so no recovery procedure had been developed for that maneuver. But just a few thousand feet above ground, Tammie Jo figured out a way to recover, only a second or two before she and her student would have been forced to eject.

The OCF teaching assignment — which she had not wanted at the time — turned out to be invaluable, and possibly the very skill that saved her and her passengers on that April morning decades later. “My worst assignment in the Navy turned out to be some of my best training,” Tammie Jo said.

A Lifetime Following Jesus

Tammie Jo credits growing up in a stable family with loving, God-fearing parents with creating the environment for her to trust in Jesus at a young age. She loved reading the Bible for its stories of heroism and courage, and the promise in the book of James to ask for wisdom encouraged her to seek God for answers. And one summer at a Christian camp, she gave her life to Christ.

She attended a Christian college with a passion to fly. Although she encountered many obstacles along the way, including being turned down by the Air Force and Army, she persevered and eventually was able to find an opening in Naval aviation.

Tammie Jo met her husband, Dean Shults, a fellow Navy pilot, at a church off base. Their relationship grew over time, and they eventually married in 1994, They have two adult children, Sydney and Marshall, who are now making their own mark in the world. The couple has served faithfully together in their church over the years. Tammie Jo volunteers at a school for at-risk children and still teaches Sunday school. They also turned a cottage on the family’s property into a temporary home for widows and for victims of Hurricane Rita.

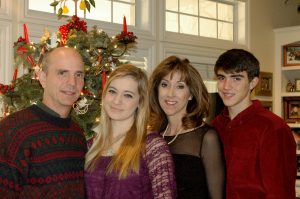

L to R: Dean, Sydney, Tammie Jo, and Marshall.

A Platform for the Savior

The accident has given Tammie Jo a platform to share her faith. “When you land a damaged airplane, people tend to listen even if you talk about something they’re not fond of. So I’ve been able to be very candid about what my foundation is. When I tell this story, God is always a part of that story. Truth, when you hear it, resonates.”

A Pioneer of Naval Aviation

Tammie Jo was one of the first female fighter pilots in the Navy, flying the F/A-18 Hornet, a twin-engine supersonic fighter jet and bomber. Although this was a groundbreaking move, it was kept low-profile because at the time there was a lot of resistance, both inside and outside the military, to women pilots in general, let alone women flying fighters. In her eight years of Navy service, Tammie Jo earned the rank of Lieutenant Commander and was awarded a National Defense Service Medal and two Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medals.

When Tammie Jo left the Navy in 1993 to return to civilian life, she flew for the Forest Service fighting forest fires in California for a summer and then was hired by Southwest Airlines. She has flown for Southwest since then. In 2000, the airline promoted her to Captain, a position she’s held for nearly two decades.

In 2018, U.S. Representative and former U.S. Air Force Colonel and pilot Martha McSally introduced a Congressional resolution honoring her for her skill and heroism on that fateful April day in 2017. Tammie Jo wrote the memoir: Nerves of Steel: How I Followed My Dreams, Earned My Wings, and Faced My Greatest Challenge, published by Thomas Nelson in October 2019. A companion Young Reader’s Edition has also released to inspire youth readers in their faith and life goals.

Grief and Lessons Learned

Tammie Jo saved the lives of 148 people in an amazing feat of aviation skill, courage, and poise. Tragically, though, Jennifer Riordan, a passenger seated next to the ruptured window in Row 14, lost her life. She had been partially pulled out through the window. Retired nurse Peggy Phillips performed CPR on her when the plane slowed enough to pull her in, but she passed away later at a hospital. Eight other passengers were injured. The NTSB investigated the accident and, on Nov. 19, 2019, released its findings and seven safety recommendations to help prevent similar tragedies in the future.